They were land animals once—four-legged, air-breathing wanderers. And then they ditched dry ground… forever. Dolphins and orcas didn’t just end up in the ocean. They made a permanent trade. Legs for fins. Grass for saltwater. Earth for endless blue. This wasn’t a casual swim—it was an evolutionary leap of no return. They still breathe air like us. But now they surf waves, dive deep, and sing in frequencies we can’t even hear. And despite millions of years passing, not one of them has tried to move back in on land. So what made them leave? And why are they never, ever coming back? This is the wild story of how two of the ocean’s smartest creatures turned their backs on land—and became masters of the sea.

Streamlined Bodies

Imagine gliding through the water with the grace of a ballet dancer. Dolphins and orcas have evolved streamlined bodies that cut through water like a hot knife through butter. Their torpedo-shaped forms reduce drag, allowing them to swim at impressive speeds.

This adaptation is crucial for hunting and escaping predators. The absence of external ears and the placement of their blowholes on top of their heads further enhance their aquatic efficiency. These features show a physical commitment to the ocean, making a return to land a cumbersome thought.

In essence, their bodies are built for the sea.

Echolocation Abilities

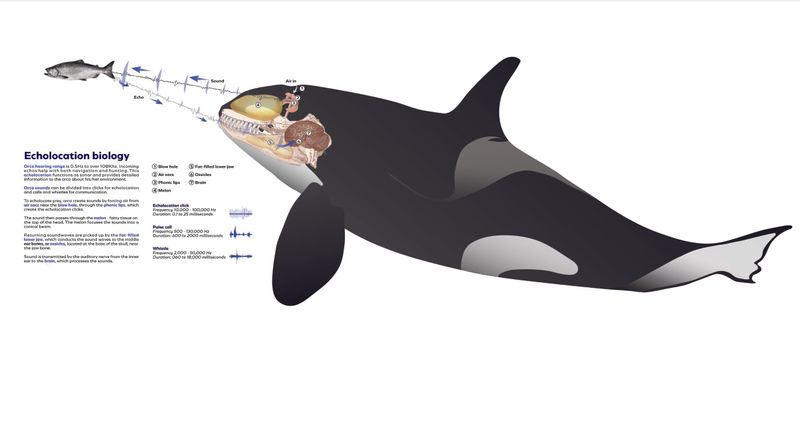

With echoes as their eyes, dolphins and orcas navigate the ocean’s depths. Their echolocation abilities are a testament to their deep-seated marine lifestyle. By emitting clicks and listening for the returning echoes, they locate prey and navigate murky waters with precision.

This natural sonar system is akin to a sixth sense, offering a survival advantage in the vast, dark ocean. On land, such a skill would be less beneficial, highlighting their deep-rooted water dependency.

Echolocation is not just a tool; it’s a lifeline, underscoring their bond with the sea.

Social Structures and Pods

In the sea, family means everything. Dolphins and orcas form tight-knit social structures known as pods. These groups are integral to their survival, offering protection, hunting assistance, and social interaction.

The bonds formed are strong, often lasting a lifetime, with intricate communication systems and cooperative behaviors. On land, such structures would face new challenges, emphasizing the adaptability to marine environments.

Their social nature is a tapestry of connections, weaving individual roles into a collective existence, perfectly tailored to ocean life.

Thermoregulation Adaptations

Surviving the ocean’s chill demands special adaptations. Dolphins and orcas possess a unique layer of blubber that insulates their bodies against cold waters. This adaptation is essential, allowing them to thrive in diverse marine climates.

Their bodies regulate temperature efficiently, balancing heat loss and retention. Such a feature is unnecessary on land, aligning with their aquatic commitment.

Blubber serves as more than an insulator; it’s an evolutionary badge of honor, signifying their allegiance to the sea and its varying temperatures.

Dietary Specializations

Feasting on the bounty of the sea, dolphins and orcas have developed dietary specializations that tie them to their oceanic home. Their diets are rich in fish, squid, and marine mammals, reflecting their position as apex predators.

This specialization requires skills and adaptations suited for hunting in water, such as speed and agility. On land, these dietary needs would be hard to meet, reinforcing their ocean-based existence.

Their role in the marine food chain is crucial, painting a picture of creatures perfectly attuned to their watery world.