Earth’s waters have been home to countless fish species throughout history. Many of these fascinating creatures are now long extinct but left behind intriguing fossil records that tell us about life in ancient times.

In this article, we explore 25 extinct fish species, each unique in its way, offering a glimpse into the diverse life forms that swam our ancient seas and rivers.

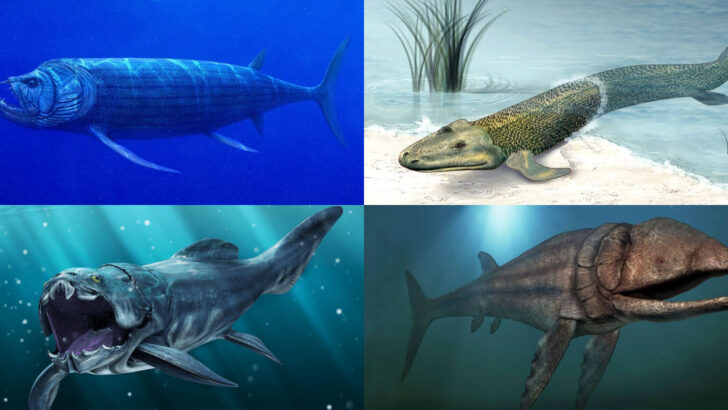

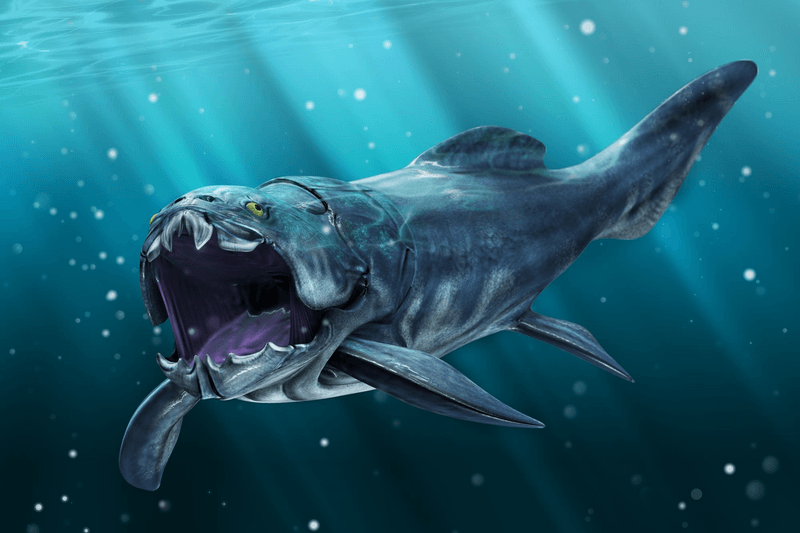

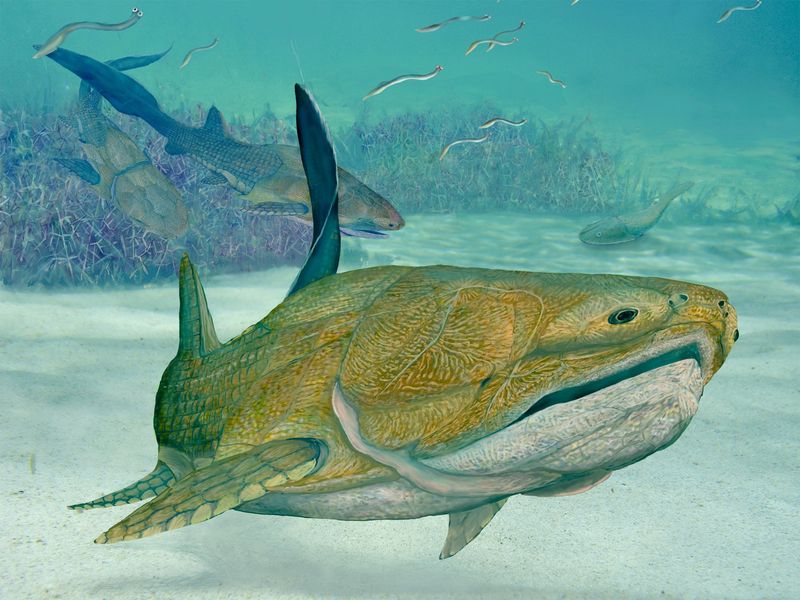

Dunkleosteus

The formidable Dunkleosteus was a prehistoric terror, boasting a heavily armored head and powerful jaws. Residing in the Devonian seas, this apex predator could grow up to 20 feet long.

Its impressive bite force allowed it to chomp through armored prey with ease, showcasing a fearsome presence in its watery domain.

Known for its distinct skeletal structure, Dunkleosteus lacked true teeth, sporting bony plates that functioned like shears. The awe-inspiring size and power of this species made it a dominant force in its ecosystem, ruling the seas for millions of years before vanishing.

Coelacanth

Thought to be extinct for millions of years, the rediscovery of the Coelacanth in 1938 shocked the scientific community. These mysterious creatures, with their lobed fins and unique body structure, are considered “living fossils.

Coelacanths possess a distinctive way of moving, akin to walking underwater, a trait not seen in many other fish species. Their discovery provided a living link to ancient times, helping scientists understand evolutionary transitions between sea and land life.

Despite their continued existence today, they remain incredibly rare, with populations vulnerable to environmental changes.

Megalodon

The Megalodon is often celebrated as one of the largest and most powerful predators in history. With teeth the size of human hands, this giant shark could grow over 50 feet long, dwarfing today’s great white sharks.

Its sheer size and strength enabled it to prey on large marine mammals with ease. Fossils suggest Megalodon had a widespread presence in ancient oceans, thriving during the Miocene and Pliocene epochs before mysteriously disappearing.

Insights into its behavior and environment are continuously sought through fossil studies, keeping this extinct titan a subject of fascination.

Leedsichthys

Leedsichthys holds the title for being one of the largest fish to have ever existed. Estimated to grow up to 65 feet long, this gentle giant was a filter feeder, sifting plankton from Jurassic seas.

Its massive size was matched by a large mouth adapted to take in vast amounts of water, enabling it to thrive in nutrient-rich environments. Leedsichthys’ existence points to the rich biodiversity of ancient oceans, where such immense creatures could sustain themselves.

The fossil record offers a tantalizing glimpse into its world, though much about its life remains a mystery.

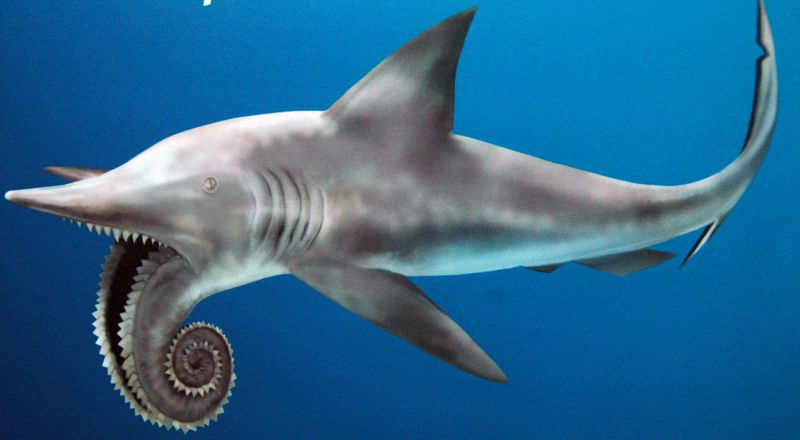

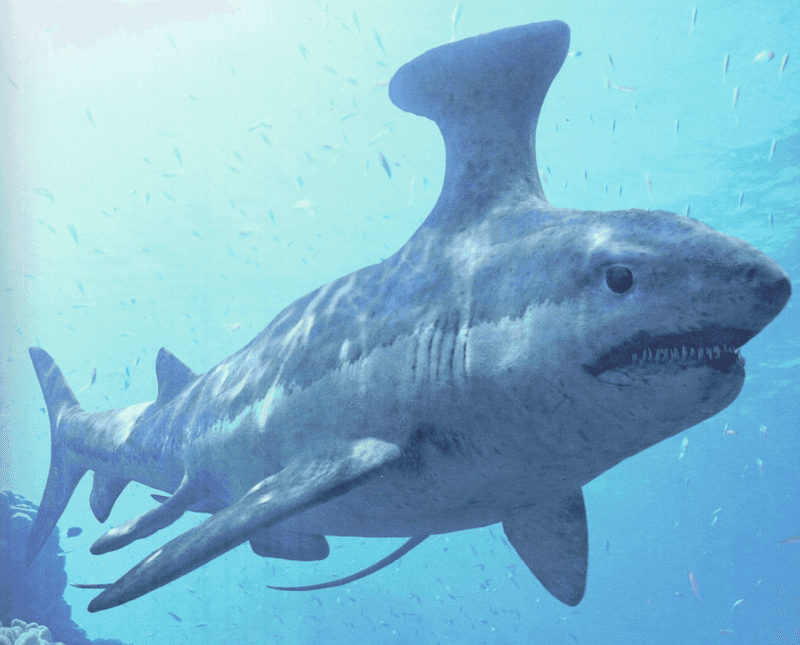

Helicoprion

Helicoprion’s bizarre spiral jaw continues to intrigue paleontologists. This ancient shark’s lower jaw featured a tooth whorl resembling a circular saw, used to capture and process prey efficiently.

Living during the Permian period, Helicoprion’s fossilized remains are primarily known from jaw structures, leaving much about its body shape speculative. The whorl’s uniqueness underscores the diverse evolutionary paths of prehistoric marine life.

Despite the limited fossil record, Helicoprion’s unusual morphology has made it a popular subject for studies on ancient marine adaptations and evolutionary experimentation.

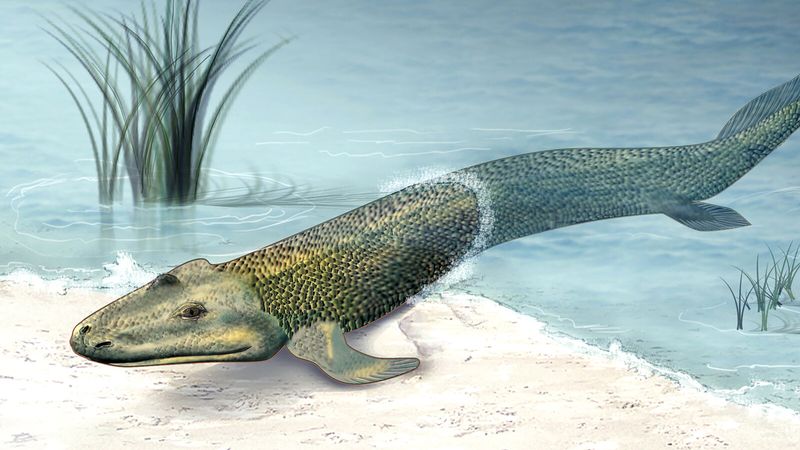

Tiktaalik

Tiktaalik represents a crucial link in the evolutionary chain between fish and tetrapods, bridging sea and land life. This extinct species, living approximately 375 million years ago, bore a mix of aquatic and terrestrial features.

Its fins contained bones akin to limbs, allowing movement in shallow water and possibly on land. The discovery of Tiktaalik fossils provided significant insight into the evolutionary transition from water to land, marking a pivotal moment in vertebrate history.

The blend of characteristics seen in Tiktaalik underscores the adaptive innovations during this transformative period.

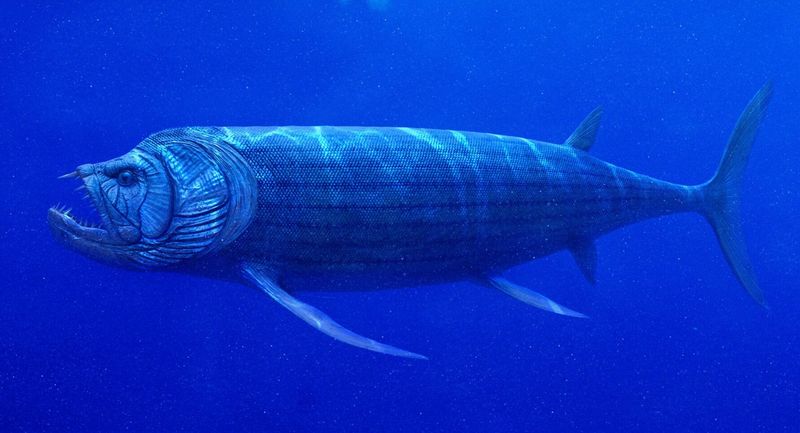

Xiphactinus

As one of the largest known bony fish from the Cretaceous period, Xiphactinus was a formidable predator, growing over 16 feet long. Its sleek, torpedo-like body allowed it to chase down prey with agility and speed.

Fossils often reveal smaller fish inside the belly of Xiphactinus, indicating its voracious appetite and hunting prowess. The predator’s well-preserved remains offer insight into the dynamic ecosystems of ancient oceans, where such formidable hunters roamed freely.

These remains serve as a testament to the rich diversity of life during the Cretaceous.

Pterichthyodes

Pterichthyodes, a small yet intriguing fish from the Devonian period, was notable for its armored body. This fish was part of the placoderm family, an early group of jawed vertebrates.

Its bony plates provided protection, a crucial adaptation in a world filled with predators. Pterichthyodes’ fossils help scientists understand the diversity and evolutionary advances of early vertebrates.

Its unique features highlight the myriad adaptations fish developed to survive in various environments, and its remains continue to inform studies on vertebrate evolution.

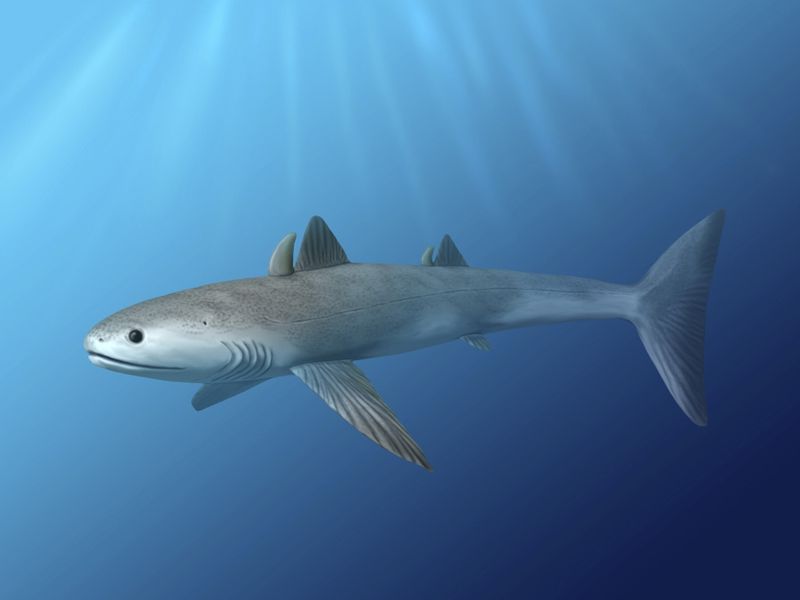

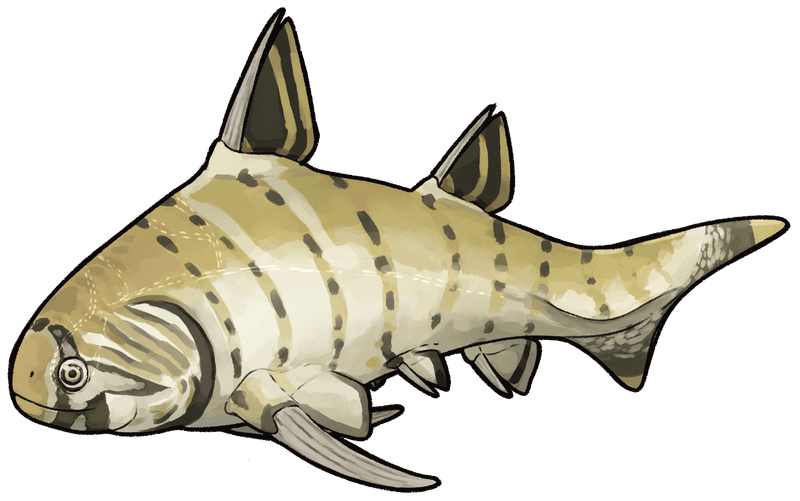

Stethacanthus

Stethacanthus stood out in ancient seas with its unusual anvil-shaped dorsal fin. This small shark, measuring around 3 feet, lived during the Devonian and Carboniferous periods.

The peculiar fin may have played a role in mating displays or as a defensive mechanism. Stethacanthus’ unique morphology reflects the vast array of evolutionary paths taken by early sharks.

The fossilized remains of this species offer a glimpse into the innovative adaptations that characterized early shark evolution, showcasing the diverse forms that ancient marine life could take.

Osteostraci

Osteostraci were jawless fish that thrived during the Silurian and Devonian periods. Known for their armored head shields, these fish lacked jaws but made up for it with a distinctive head structure.

Their bony plates provided protection against predators in ancient waters. The study of Osteostraci fossils provides valuable insights into the evolution of early vertebrates, particularly the development of protective adaptations.

Their existence highlights the diversity of early fish species and the various evolutionary strategies employed to thrive in prehistoric environments.

Anomalocaris

Though not technically a fish, Anomalocaris was a significant marine predator during the Cambrian period. Its segmented body and rudimentary limbs set it apart in the ancient seas, where it hunted trilobites and other small creatures.

Anomalocaris’ unique anatomy challenges traditional definitions of early marine life, showcasing the wide array of life forms that existed in prehistoric oceans. Its fossils provide crucial insights into the Cambrian explosion, a period marked by rapid diversification of life.

The legacy of Anomalocaris continues to influence our understanding of early marine ecosystems.

Cladoselache

Cladoselache is one of the earliest known sharks, living in the Devonian period. With a sleek, streamlined body, this shark measured around 6 feet long and was a swift hunter in ancient seas.

Unlike many modern sharks, Cladoselache lacked scales and had a different fin structure, which contributed to its agile swimming capabilities. Its well-preserved fossils provide key insights into early shark evolution and the adaptations that have persisted through millennia.

Cladoselache’s existence marks a critical point in the evolutionary history of sharks, setting the stage for future developments.

Diplacanthus

Diplacanthus was a small, spiny-finned fish that lived during the Devonian period. Its distinctive spines set it apart, serving as both a defensive mechanism and a way to navigate its watery environment.

This ancient fish’s fossils are instrumental in understanding the diversity of early acanthodians, a group known as “spiny sharks. ” Despite its small size, Diplacanthus contributed to the rich tapestry of life in the Devonian seas.

The study of its remains helps piece together the evolutionary puzzle of early vertebrate development, shedding light on the complexity of ancient marine life.

Hyneria

Hyneria was a formidable freshwater predator during the Devonian period. Growing up to 12 feet long, it was one of the largest predatory fish of its time, with powerful jaws capable of capturing sizable prey.

Its habitat in ancient rivers and lakes offered abundant resources, making it a dominant figure in its ecosystem. The discovery of Hyneria fossils has provided valuable context for understanding the structure and dynamics of ancient freshwater environments.

These insights continue to inform studies of Devonian ecosystems and the evolutionary pathways of predatory fish.

Acanthodes

Acanthodes was a small fish known for its spiny fins and streamlined body, thriving in the Permian period. Measuring up to 12 inches, it was part of the acanthodian group, often referred to as “spiny sharks.

Its fossils are frequently found in ancient marine and freshwater deposits, indicating versatility in habitats. The structure of Acanthodes’ fins offers clues about the evolutionary adaptations that helped early fish succeed in diverse environments.

While small, its role in the ecosystem was significant, contributing to the intricate web of Permian marine life.

Basilosaurus

Although not a fish, Basilosaurus was a remarkable marine mammal from the Eocene epoch. Its elongated body and large size, reaching up to 60 feet, made it a dominant predator in ancient seas.

Initially mistaken for a reptile due to its serpent-like appearance, Basilosaurus was later identified as an early whale, providing key insights into cetacean evolution. Its fossils have been instrumental in understanding the transition of life from land to sea, highlighting the diverse evolutionary adaptations in ancient marine environments.

Basilosaurus remains a fascinating subject for paleontologists.

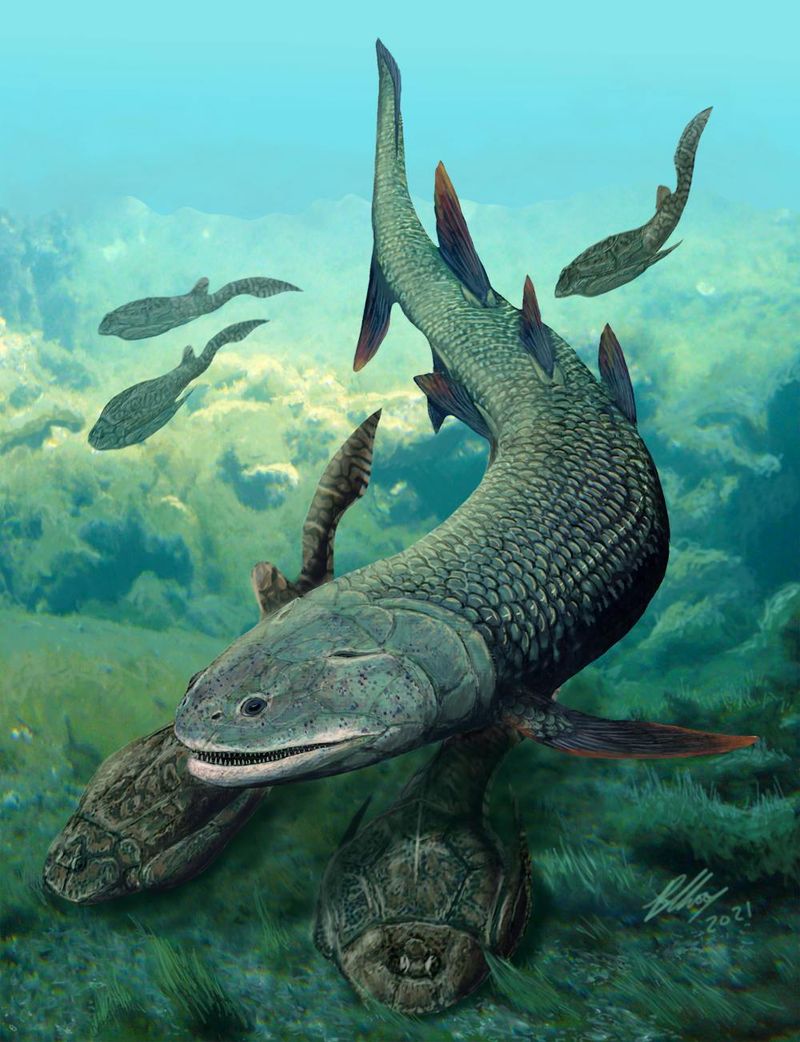

Gogonasus

Gogonasus serves as a critical link in the evolutionary journey from fish to tetrapods. This Devonian species displayed a unique blend of features, including both fish-like and early tetrapod characteristics, aiding its adaptation to changing environments.

Its discovery provided essential evidence of the evolutionary steps leading to life on land. The structural adaptations seen in Gogonasus highlight the complex evolutionary processes that enabled vertebrates to explore new ecological niches.

The fossilized remains of Gogonasus continue to illuminate the intricate pathways of vertebrate evolution.

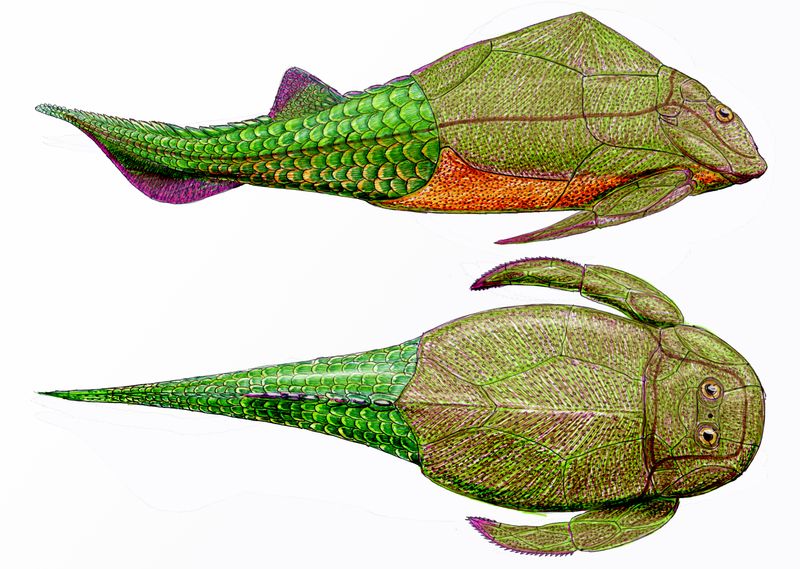

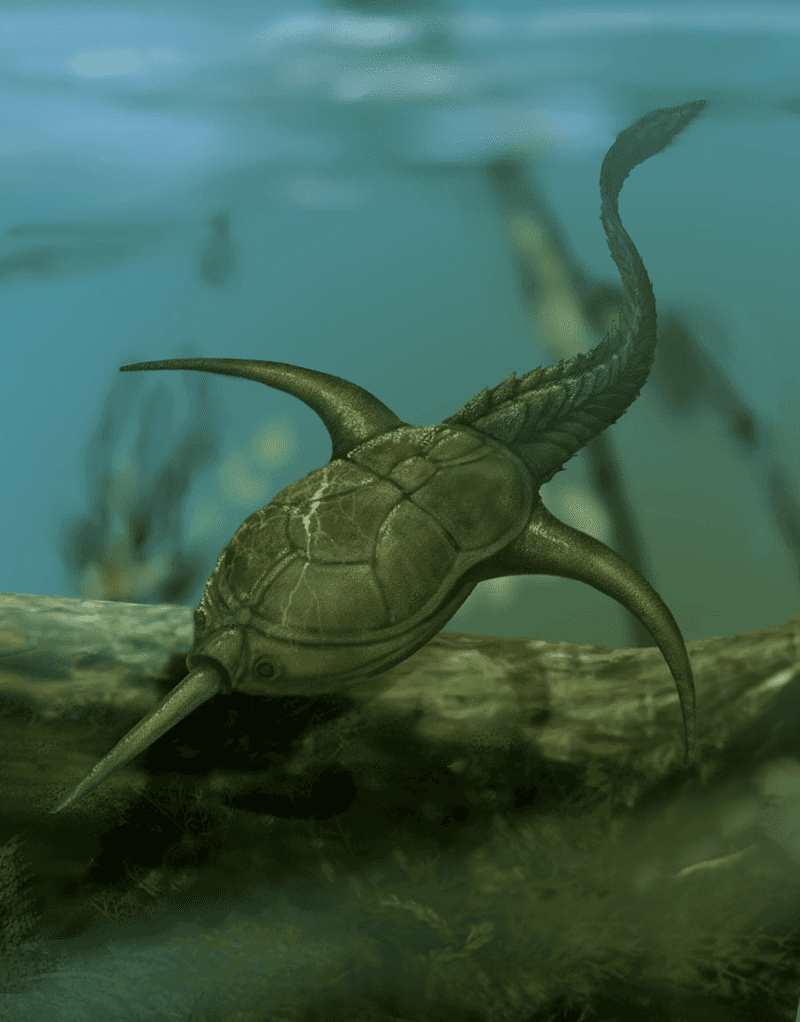

Bothriolepis

Bothriolepis was a widespread placoderm that thrived in Devonian freshwater environments. Its heavily armored body provided defense against predators, a common adaptation among placoderms.

With a global distribution, Bothriolepis’ fossils are found across multiple continents, reflecting its success in diverse habitats. The study of its remains offers insights into the evolutionary history of armored fish and the ecological dynamics of Devonian freshwater systems.

Despite its extinction, Bothriolepis continues to interest researchers, serving as a window into the past world’s ancient aquatic life.

Entelognathus

Entelognathus is a pivotal species in the history of jawed vertebrates, living during the late Silurian period. Its remarkably well-preserved fossils reveal an armored head, showcasing the early development of jaws.

This discovery has reshaped understanding of vertebrate evolution, suggesting that complex jaw structures emerged earlier than previously thought. Entelognathus’ unique anatomy provides valuable clues about the evolutionary innovations that led to modern jawed vertebrates.

The insights gained from studying this species continue to influence theories about the origins and diversification of early vertebrates.

Gemuendina

Gemuendina was a peculiar fish with a flattened body and an armored head, living during the Devonian period. Its unique shape suggests adaptations for life near the seabed, possibly feeding on small organisms within the sediment.

The armored head offered protection, a characteristic seen in many Devonian fish. Gemuendina’s fossils provide a snapshot of the diverse life forms inhabiting ancient seas and the varying adaptations that evolved.

The exploration of Gemuendina’s life and environment enriches our understanding of the ecological landscapes of prehistoric marine ecosystems.

Acanthostega

Acanthostega occupies a crucial place in the evolutionary narrative, bridging the gap between aquatic and terrestrial life. This early tetrapod, living in the Devonian period, possessed limbs with digits, a significant step towards terrestrial adaptation.

Its anatomy reveals a blend of fish and amphibian characteristics, underscoring the complexities of early vertebrate evolution. The fossil record of Acanthostega offers critical insights into the transition from water to land, illustrating the innovative adaptations that occurred during this pivotal period.

Its discovery continues to shape our understanding of life’s evolutionary history.

Coccosteus

Coccosteus was a notable placoderm from the Devonian period, recognized for its armored body that safeguarded against predators. Measuring about 16 inches, it thrived in various marine environments.

The discovery of well-preserved fossils has provided valuable insights into the anatomy and lifestyle of early jawed vertebrates. Coccosteus serves as a key species for understanding the evolutionary pathways of placoderms, highlighting the diverse adaptations that occurred in prehistoric seas.

The continued study of Coccosteus enriches our knowledge of ancient marine life and evolutionary history.

Doryaspis

Doryaspis was a jawless fish that lived in the Devonian seas, known for its elongated body and specialized head shield. This unique anatomy provided both protection and a hydrodynamic advantage in its aquatic environment.

As part of the heterostracan group, Doryaspis’ fossils contribute to our understanding of early vertebrate diversity and evolutionary strategies. The intricate features of its armor and body structure highlight the evolutionary experimentation that characterized the Devonian period.

The study of Doryaspis continues to inform theories about the development of early aquatic vertebrates.

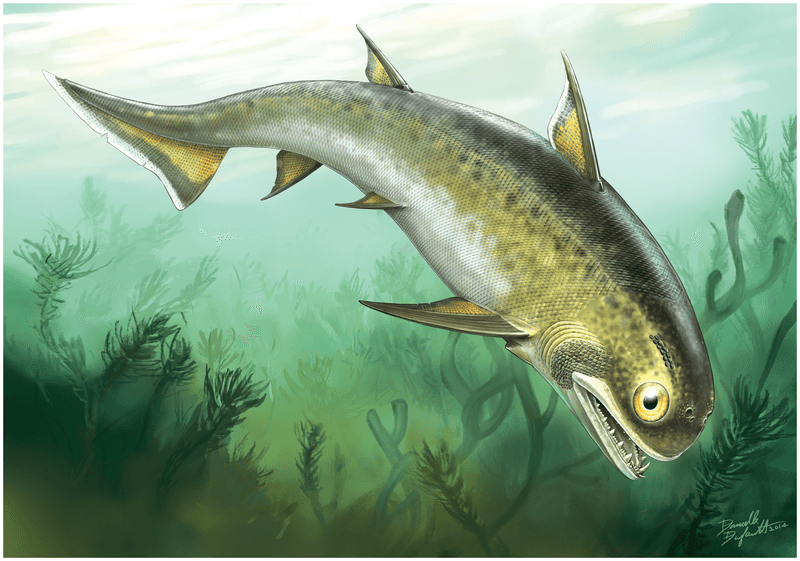

Eusthenopteron

Eusthenopteron is often celebrated as a precursor to tetrapods, showcasing traits that foreshadowed the move from water to land. This Devonian lobe-finned fish possessed bones in its fins similar to those in tetrapod limbs.

Its well-preserved fossils have been pivotal in understanding the evolutionary transition to terrestrial life. Eusthenopteron represents a key stage in vertebrate history, highlighting the intricate changes that facilitated the colonization of land by early vertebrates.

The study of this species continues to influence insights into evolutionary biology and the progression of life on Earth.

Arandaspis

Arandaspis, an intriguing jawless fish, roamed the Ordovician seas over 450 million years ago. This early vertebrate, found primarily in what is now Australia, had a streamlined body covered in bony plates.

Unlike modern fish, Arandaspis lacked a jaw, instead using its mouth to filter microscopic organisms from the water. Its armor-like plating offered protection from predators, a key feature for survival in its prehistoric habitat.

Understanding Arandaspis helps scientists trace the evolutionary history of vertebrates. Its unique characteristics provide insights into the adaptations that allowed early fish to thrive in ancient waters.