We didn’t just lose animals—we lost solutions.

When certain species vanished, they didn’t just disappear from the food chain.

They took their superpowers with them.

Pest control. Forest maintenance. Carbon capture. Even climate regulation.

What if we could rewind time and bring some of them back?

From towering herbivores that kept grasslands in check to deep-diving giants that fertilized the ocean, these extinct animals weren’t just part of nature—they were nature’s engineers.

And now? Their absence is being felt in ways we’re only beginning to understand.

Imagine a world where these creatures still roamed, doing the dirty work of rebalancing ecosystems and healing the planet—no tech required.

Here are ten animals that, if they were still here, might just help us fix the mess we’re in.

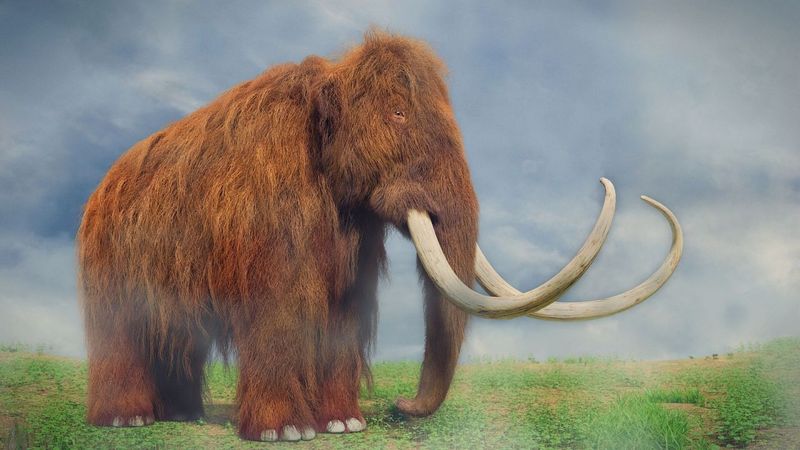

Woolly Mammoth

Imagine a world where woolly mammoths once again roamed the tundra. These colossal creatures played a crucial role in maintaining Arctic ecosystems by trampling down snow, allowing cold air to penetrate the ground.

This process helped keep permafrost frozen, trapping greenhouse gases. With permafrost now thawing, their absence is keenly felt. Bringing them back could slow climate change.

Fun fact: Mammoths were more closely related to modern elephants than mastodons. These gentle giants were social creatures, living in herds led by matriarchs. Reintroducing them could restore a lost link in the chain of Arctic life.

Aurochs

The aurochs, ancestors of modern cattle, were once widespread across Europe. These impressive herbivores played a vital role in maintaining open landscapes, preventing overgrowth.

Their grazing habits promoted biodiversity by creating diverse habitats for various species. Reintroducing aurochs could support the recovery of grasslands and forests, curbing the spread of woody plants.

Did you know? The last known aurochs died in Poland in 1627. Conservationists are now attempting to breed back similar cattle to restore these ecosystems. Their legacy continues in the Bos primigenius, showcasing the importance of large grazers in nature.

Tasmanian Tiger

The Tasmanian tiger, or thylacine, was a unique marsupial predator native to Tasmania. It played a critical role in controlling prey populations and maintaining ecological balance.

Since their extinction in the 20th century, we’ve seen an increase in invasive species that threaten native wildlife. Reintroducing the thylacine could help manage these populations.

Interestingly, despite its nickname, it was more closely related to kangaroos than tigers. Its distinctive striped back made it a fascinating creature. Restoring the thylacine could revitalize Australia’s natural heritage and bolster biodiversity.

Passenger Pigeon

Once numbering in the billions, passenger pigeons were keystone species in North American forests. They played a key role in seed dispersal, promoting forest growth.

Their extinction in the early 20th century left a significant gap in the ecosystem. Reviving these birds could rejuvenate forests and increase carbon sequestration. Did you know? A single flock could darken the sky for miles and consisted of millions of pigeons.

Reintegrating them would support various plant species, enhancing biodiversity and forest health. Their story is a stark reminder of the impact of unchecked human activity.

Steller’s Sea Cow

Steller’s sea cow was a gigantic marine herbivore that once inhabited the cold waters of the North Pacific. These docile creatures fed on kelp, maintaining the health of underwater meadows.

Their absence has led to overgrowths that disrupt marine ecosystems. Reintroduction could balance these environments and support marine biodiversity.

Fun fact: They were discovered by Europeans in 1741 and hunted to extinction within 27 years. These gentle giants symbolize the fragile nature of marine life. Restoring them could help stabilize oceanic food webs and foster a healthier maritime world.

Great Auk

The great auk was a flightless bird native to the North Atlantic coastlines. It was an important predator, controlling fish populations and supporting marine biodiversity.

Since its extinction in the mid-19th century, marine ecosystems have felt its loss. Bringing them back could help regulate fish stocks and restore ecological harmony.

Did you know? Great auks were excellent swimmers, using their wings to navigate underwater. Their black and white plumage earned them the nickname ‘penguins of the north.’ Reintroducing them could revive coastal habitats and support fishing communities.

Dodo

The dodo, extinct since the late 17th century, was endemic to Mauritius. As ground-nesting birds, they played a role in seed dispersion, promoting plant growth.

Their extinction disrupted the island’s ecology, leading to the decline of certain tree species. Restoring the dodo could support forest regeneration and biodiversity.

Fun fact: Dodos were closely related to pigeons, despite their unusual appearance. Their story serves as a powerful lesson in the fragility of island ecosystems. Reintroducing them could mend the ecological rift left by their disappearance.

Caribbean Monk Seal

Caribbean monk seals once thrived in warm waters, playing a role in maintaining coral reef health. Overfishing and hunting led to their extinction in the 20th century.

These seals were key predators, controlling fish populations that directly affect coral health. Their reintroduction could help restore balance and support reef recovery.

Interestingly, they were the only seal species native to the Caribbean Sea. Reviving them could boost marine tourism and conservation efforts, offering a hopeful future for the region’s rich aquatic life.

Quagga

The quagga, a subspecies of plains zebra, was known for its unique stripe pattern. Native to South Africa, it was a grazer that helped maintain grassland ecosystems. Since its extinction in the late 19th century, the balance in these habitats has shifted.

Reviving the quagga could support biodiversity and control bush encroachment. Did you know? Efforts are underway to selectively breed zebras to recreate their appearance and ecological role.

Reintroducing quaggas could restore grasslands and benefit coexisting species. Their story highlights the importance of each species in their natural environment.

Pyrenean Ibex

The Pyrenean ibex, once native to the Pyrenees mountains, was a nimble herbivore that thrived in rocky terrains. They played a role in shaping vegetation by grazing on shrubs and grasses, promoting plant diversity.

Their extinction in the early 2000s marked a loss for these mountain ecosystems. Cloning efforts nearly revived them briefly, highlighting scientific advancements. Restoration could enhance biodiversity and support ecological balance in mountainous regions.

Did you know? The Pyrenean ibex was the first species to undergo de-extinction, albeit shortly. Their story captures both loss and hope in conservation.