Snakes didn’t just slither across ancient lands—they slithered straight into the heart of human imagination.

From deserts to jungles, icy mountains to river valleys, civilizations across the world wove snakes into the very story of existence.

These creatures weren’t just background characters; they were gods, guardians, destroyers, and creators, all coiled into one powerful symbol.

Some saw the snake as the keeper of secret knowledge.

Others feared it as the trickster that tipped the world into chaos.

In every case, the serpent wasn’t just an animal—it was a force of cosmic drama.

Get ready to meet the civilizations that saw the universe through the glint of a serpent’s eye.

Their myths are wild, beautiful, terrifying—and once you hear them, you’ll never look at a snake the same way again.

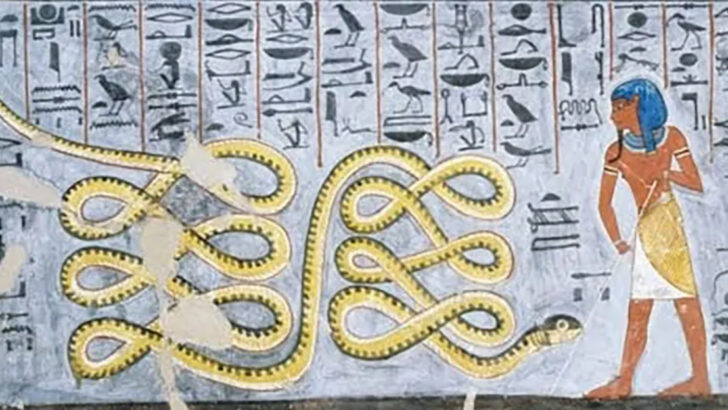

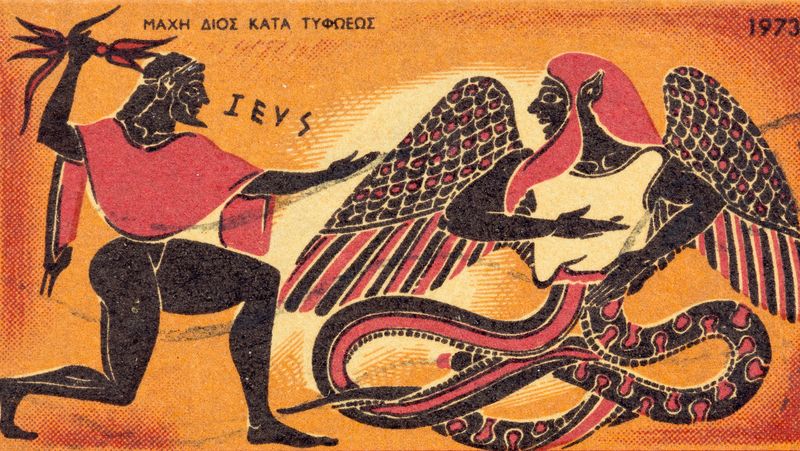

Egyptian Civilization

In the Egyptian creation myth, Atum, the sun god, is often depicted as a serpent. Atum emerged from the primordial waters of chaos, known as Nun. Envisioned as a serpent, he brought order to chaos. Atum created the next generation of gods by spitting or releasing them from his own body, symbolizing life and creation.

The image of the snake is intertwined with eternity in Egyptian mythology. The ouroboros, a snake eating its tail, represents the endless cycle of life and death, a testament to the eternal nature of life in Egyptian belief.

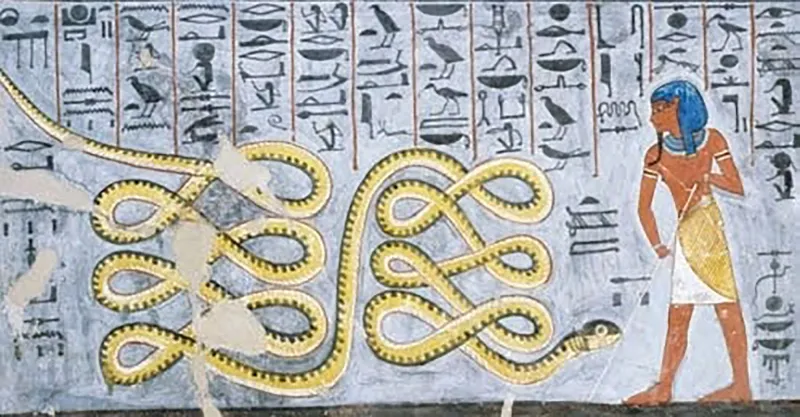

Mesopotamian Civilization

Mesopotamian mythology introduces Tiamat, a primordial goddess and serpent-like dragon. She embodies chaos and is a central figure in the Babylonian creation epic, the Enuma Elish. In this myth, Tiamat battles the younger gods, led by Marduk. Her defeat leads to the creation of the world from her divided body.

The Mesopotamian depiction of Tiamat as a vast serpent symbolizes the untamed, primal forces of the universe. Tiamat’s story illustrates the struggle between order and chaos, a recurring theme in Mesopotamian mythos. Her narrative underscores the transformation from chaos to order.

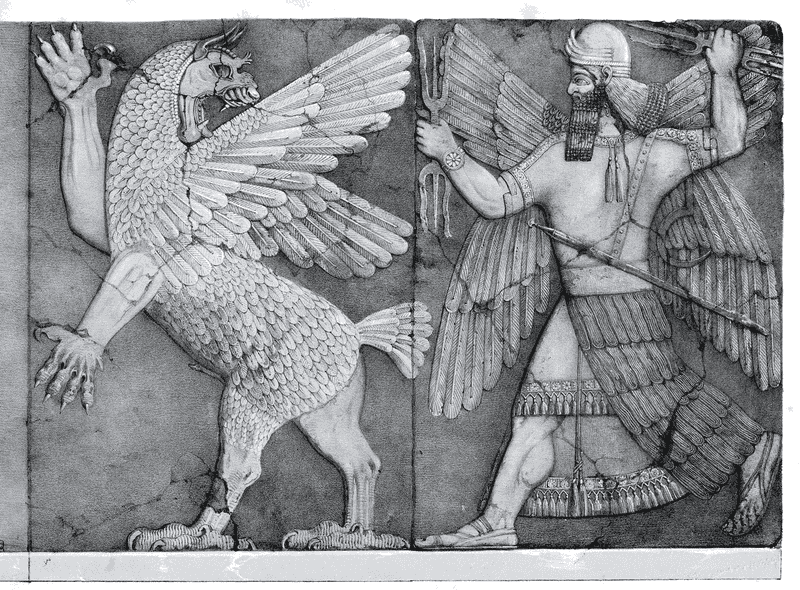

Greek Civilization

In Greek mythology, Typhon is a fearsome serpent-like creature, often considered the father of all monsters. A mighty adversary, he challenged Zeus, the king of the gods, in a titanic battle. Typhon’s hundred dragon heads belched fire, threatening the cosmos.

Zeus eventually defeated Typhon, trapping him beneath Mount Etna. The serpent’s fiery breath is said to cause the volcano’s eruptions. Typhon symbolizes the ultimate chaos and disorder, while Zeus represents divine order. This epic battle reflects the Greek philosophical theme of balance between chaos and order.

Norse Civilization

In Norse mythology, Jormungandr, also known as the Midgard Serpent, is a colossal snake that encircles the Earth. This fearsome creature is one of Loki’s children and is prophesied to play a crucial role during Ragnarok, the end of the world.

The serpent’s vastness symbolizes the wild and untamed forces of nature. When Jormungandr releases his tail, Ragnarok will begin, leading to a cosmic battle that ends the world. The Norse myths use Jormungandr to illustrate themes of inevitability and cyclical destruction, reflecting on the transient nature of existence.

Aztec Civilization

The Aztecs revered Quetzalcoatl, a feathered serpent deity symbolizing wisdom, wind, and life. As a creator god, he was instrumental in the formation of humans and the cosmos. Quetzalcoatl’s dual nature as both bird and snake embodies the connection between the heavens and earth.

According to Aztec mythology, he created humanity from the bones of previous races, giving them life with his own blood. Quetzalcoatl’s symbolism reflects rebirth, renewal, and the harmony of opposites. His imagery as a feathered serpent highlights the blend of divine and earthly attributes in Aztec culture.

Chinese Civilization

In Chinese mythology, Nuwa is a goddess with the lower body of a serpent. She is credited with creating humanity from clay and repairing the pillars of heaven after a great catastrophe. Her serpent form signifies fertility and the cyclical nature of life.

Nuwa’s myth underscores the themes of creation and restoration. Her actions ensured the survival of humanity and the cosmos. The imagery of her serpent form is rich with symbolism, representing transformation and the earth’s nurturing qualities, highlighting the interconnectedness of creation and life in Chinese thought.

Hindu Civilization

In Hindu mythology, Vishnu is often depicted reclining on the serpent Ananta, floating on the cosmic ocean. Ananta, meaning endless, symbolizes eternity and the infinite nature of time. The serpent’s coils represent cycles of creation and destruction.

Vishnu’s repose on Ananta signifies the preservation of the universe during the cosmic rest between creations. This imagery captures the balance between chaos and order, continuity and change. Ananta’s presence in the creation myth portrays the eternal support sustaining the cosmos, a central tenet of Hindu cosmology.

Mayan Civilization

Kukulkan, the feathered serpent god of the Maya, is a symbol of transformation and the sky. This deity is associated with the planet Venus and represents the cycles of time and celestial events. Kukulkan is often depicted descending from the heavens, linking the divine with the earthly realm.

The temple of El Castillo at Chichen Itza is famous for the shadow of Kukulkan, appearing as a serpent on the equinox. His myth reflects the Mayan understanding of astronomy and the interconnectedness of life and the universe. Kukulkan’s serpent form highlights themes of rebirth and renewal.

Celtic Civilization

In Celtic mythology, serpents are revered as symbols of wisdom, fertility, and the sacred earth. The serpent goddess, often linked with the earth, embodies transformation and the cycle of life. Celtic art frequently features serpents intertwined with knot designs, representing the interconnectedness of life.

These serpents serve as guardians of sacred sites and are believed to possess healing powers. The serpent’s presence in Celtic myth underscores themes of renewal and the eternal cycle of nature. Their depiction in art and lore highlights the balance between the earthly and spiritual worlds, a key aspect of Celtic belief.

Zoroastrian Civilization

In Zoroastrian mythology, Azhi Dahaka is a monstrous three-headed serpent demon representing evil and destruction. This creature is a central figure in ancient Persian lore, embodying chaos and opposition to the divine order.

Azhi Dahaka’s story is a reminder of the constant battle between good and evil, a core theme in Zoroastrianism. The serpent’s defeat by the hero Thraetaona symbolizes the triumph of order and righteousness over chaos. This narrative reflects the eternal struggle between light and darkness, reinforcing moral and cosmic dualities within Zoroastrian beliefs.

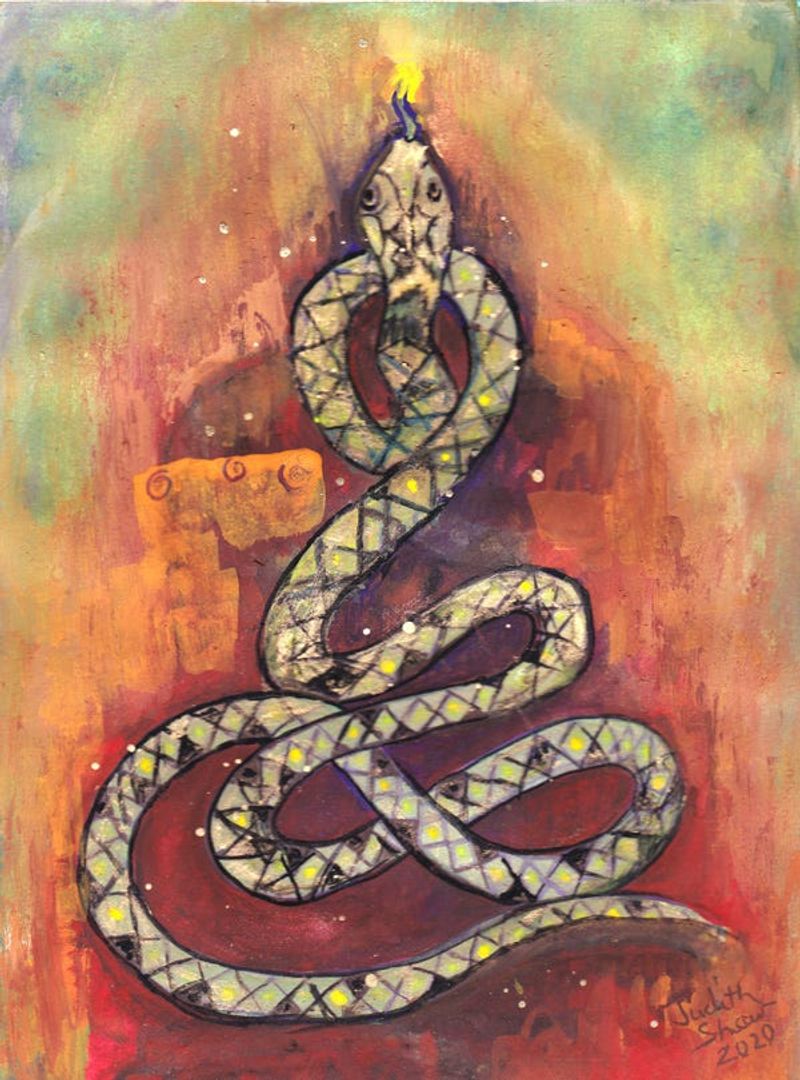

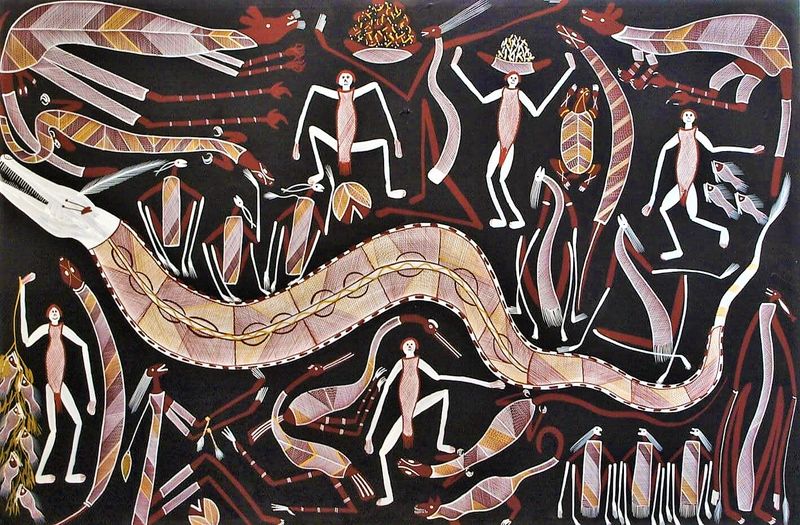

Aboriginal Australian Cultures

The Rainbow Serpent is a prominent figure in the creation myths of Aboriginal Australian cultures. This powerful being is associated with water, fertility, and creation. The serpent’s movements across the land created rivers and shaped the landscape.

The Rainbow Serpent symbolizes the life-giving forces of nature and the connection between the physical and spiritual realms. Its myth highlights the importance of water and the environment in sustaining life. The Rainbow Serpent’s presence in Aboriginal culture underscores themes of renewal and the sacred relationship with the natural world.

Japanese Civilization

In Japanese mythology, Yamata no Orochi is an enormous eight-headed serpent defeated by the storm god Susanoo. Each of its heads corresponds to a different region, embodying natural forces and chaos.

The serpent’s defeat led to the discovery of the sword Kusanagi, a symbol of imperial authority. This myth illustrates themes of heroism and the triumph of order over chaos. Yamata no Orochi’s dramatic tale highlights the importance of bravery and divine intervention in Japanese folklore, reflecting the cultural values of strength and perseverance.

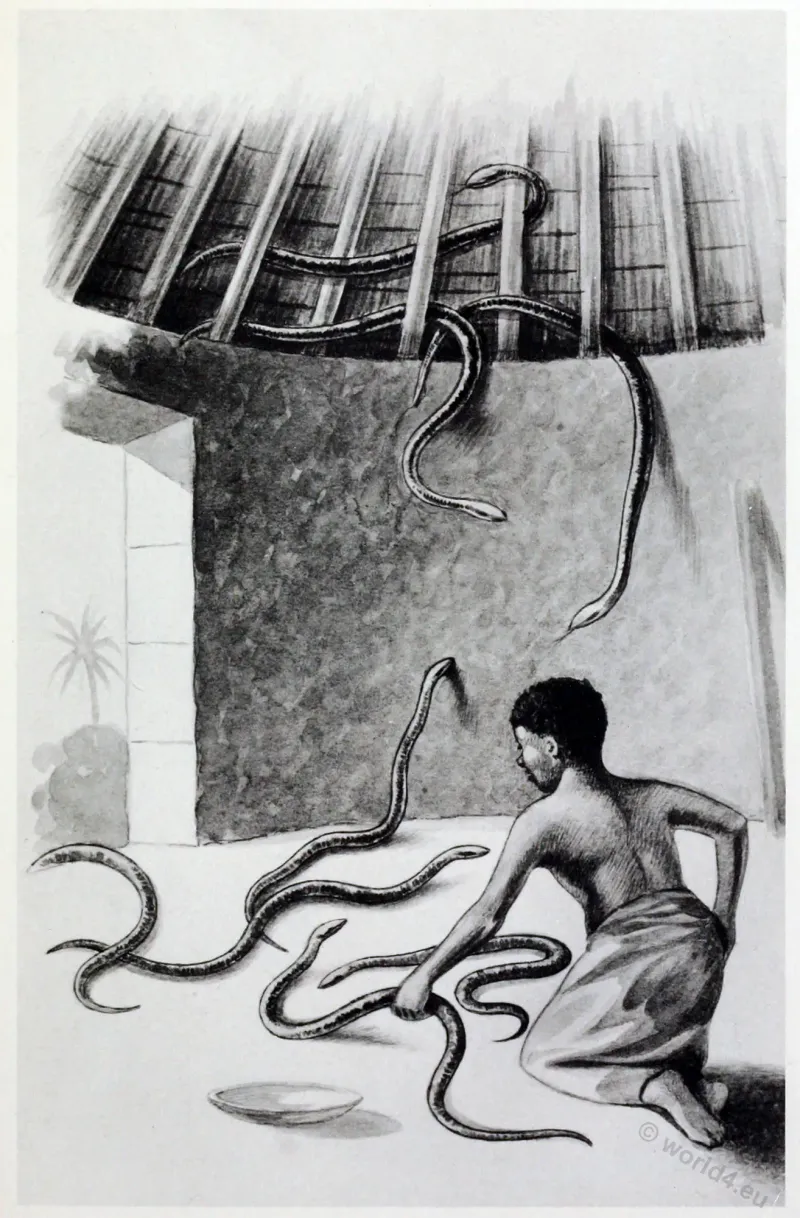

African Cultures (Dahomey)

In the mythology of the Dahomey people of Africa, Danh-gbi is a revered serpent god associated with fertility and the earth. Believed to be the progenitor of the earth and life, his coils are said to support the heavens.

Danh-gbi’s presence in creation myths symbolizes the connection between the divine and natural worlds. The serpent’s role in the cycle of life reflects themes of regeneration and continuity. In Dahomey culture, Danh-gbi represents the sustaining forces of nature, embodying the harmony between humanity and the environment.

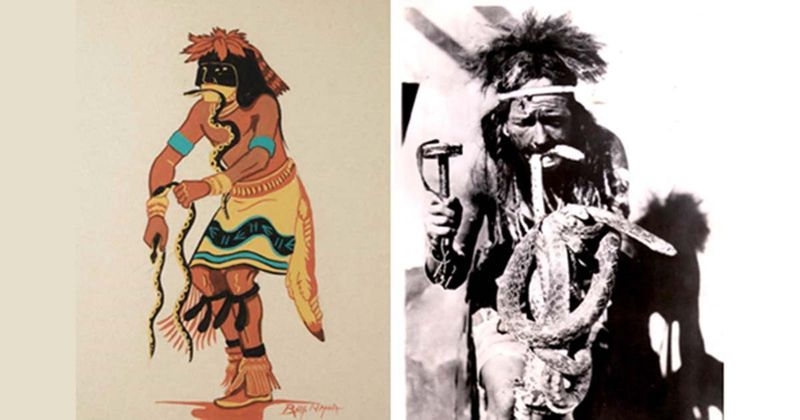

Native American Cultures (Hopi)

In Hopi culture, the Snake Dance is a ceremonial ritual honoring the snakes as symbols of life and renewal. The dance is performed to bring rain and ensure a bountiful harvest. During the ceremony, participants handle live snakes, embodying the connection between the Hopi people and the natural world.

The serpent in Hopi mythology represents the cycles of life and the vital forces of nature. This tradition emphasizes themes of harmony and balance with the environment. The Snake Dance reflects the Hopi’s deep spiritual connection to the land and their reverence for life-giving forces.