Imagine a time when creatures the size of skyscrapers roamed the Earth. These ancient giants, now long extinct, have left behind fossils that continue to captivate and amaze us. Their enormous size and unique features have forever altered our understanding of prehistoric life.

From massive dinosaurs to colossal mammals, these creatures weren’t just big—they were groundbreaking. Their fossilized remains have unlocked secrets about evolution, ecosystems, and the world that once was.

Join us as we journey through history to meet 16 of the most awe-inspiring ancient giants whose fossils changed everything we thought we knew about life on Earth. Ready to step back in time and see the world as it was millions of years ago?

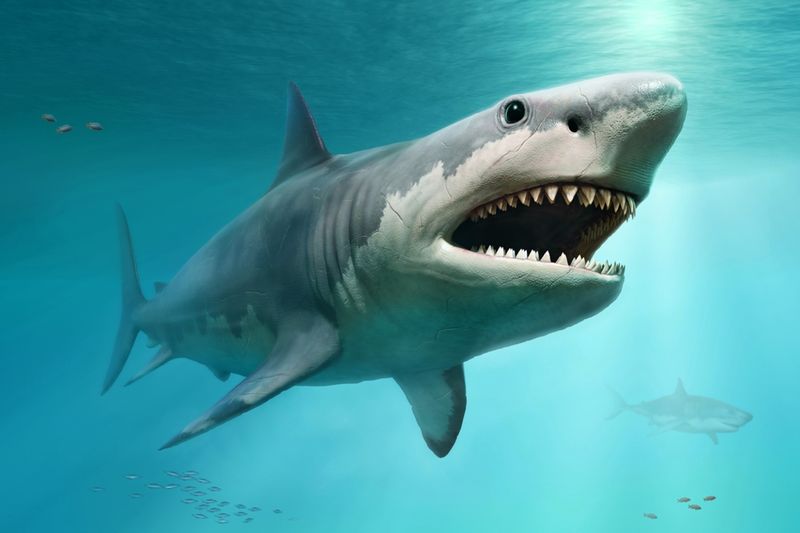

Megalodon

The Megalodon was a formidable predator of the ancient seas, dwarfing the great white shark. Known for its massive teeth, some the size of a human hand, it terrorized the oceans more than 23 million years ago.

This giant shark could reach lengths of up to 60 feet, a size that allowed it to prey on large marine mammals. Fossilized teeth provide evidence of its presence and dominance.

These fossils have reshaped our understanding of oceanic food chains in prehistoric times, highlighting the diversity and complexity of ancient marine ecosystems.

Titanoboa

Titanoboa, the largest snake ever discovered, slithered through the tropical rainforests of what is now Colombia. Measuring up to 42 feet long, it weighed over a ton. This serpentine behemoth thrived shortly after the extinction of the dinosaurs.

Its fossils reveal much about post-dinosaur ecosystems and the evolution of snakes. Titanoboa’s immense size suggests it preyed on large reptiles and mammals, possibly even crocodiles.

Its discovery has led to new insights into the climatic conditions of the Paleocene epoch, providing crucial information about the Earth’s ancient climate and environments.

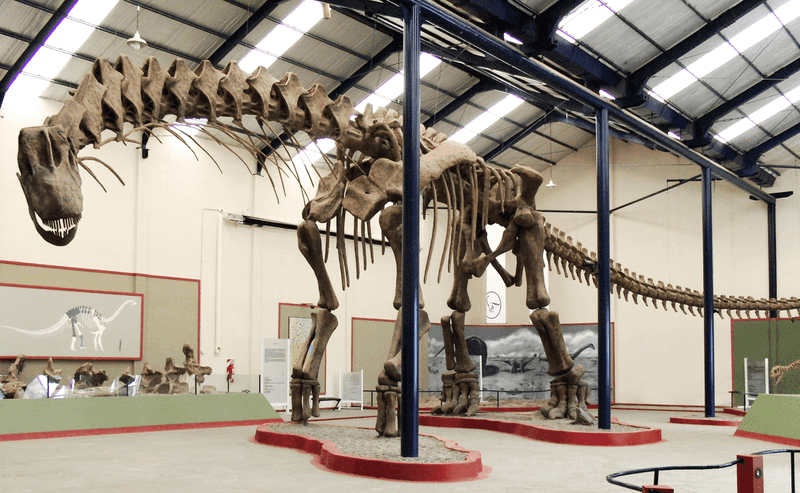

Argentinosaurus

Argentinosaurus, one of the largest known land animals, roamed what is now South America during the Late Cretaceous period. With estimates suggesting lengths of up to 100 feet, this herbivorous giant weighed as much as 100 tons.

Its massive size offered protection from predators and allowed it to reach high vegetation. Fossils of Argentinosaurus have illuminated the understanding of sauropod biology and locomotion.

These fossils provide a window into the life of dinosaurs, illustrating their adaptation and evolution in an ever-changing prehistoric world.

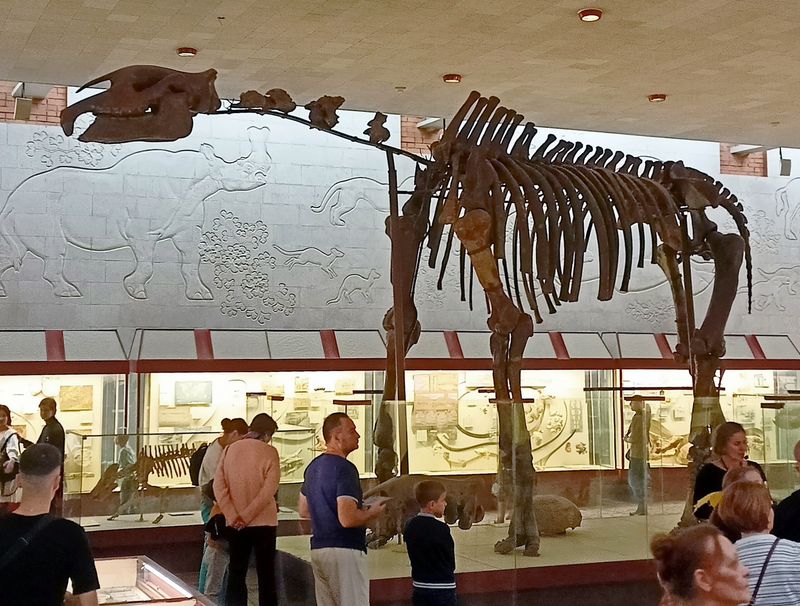

Paraceratherium

Paraceratherium, the giant of land mammals, lived approximately 34 million years ago. With a height exceeding 16 feet at the shoulder and weighing over 20 tons, it was the largest land mammal to have ever lived.

Its fossils, primarily found in Asia, depict an animal without any known predators due to its sheer size. These remains have enriched the understanding of mammalian evolution and adaptation.

By examining Paraceratherium, scientists have gained insights into the evolution of herbivorous mammals and their ecological roles in ancient environments.

Deinosuchus

Deinosuchus, the ‘terrible crocodile,’ was a giant ancestor of modern crocodiles. Living 80 to 73 million years ago, it inhabited the coasts of North America. It could grow up to 33 feet long, making it one of the most formidable predators of its time.

Fossils show it hunted large dinosaurs, evidenced by bite marks on dinosaur bones. Its existence offers a glimpse into the predatory dynamics of the Cretaceous period.

These insights are crucial for understanding ancient ecosystems and the evolutionary history of crocodiles.

Giganotosaurus

Giganotosaurus, a carnivorous dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous, was one of the largest terrestrial predators. Found in South America, it reached lengths of up to 43 feet. Its fossils have provided insights into the evolution of predatory dinosaurs.

Giganotosaurus was a top predator, preying on large herbivorous dinosaurs. The discovery of this dinosaur has been vital in understanding the ecosystem dynamics of the Cretaceous period.

Its size and predatory nature reflect the complex interplay between predators and prey in ancient times, shedding light on the biodiversity of prehistoric ecosystems.

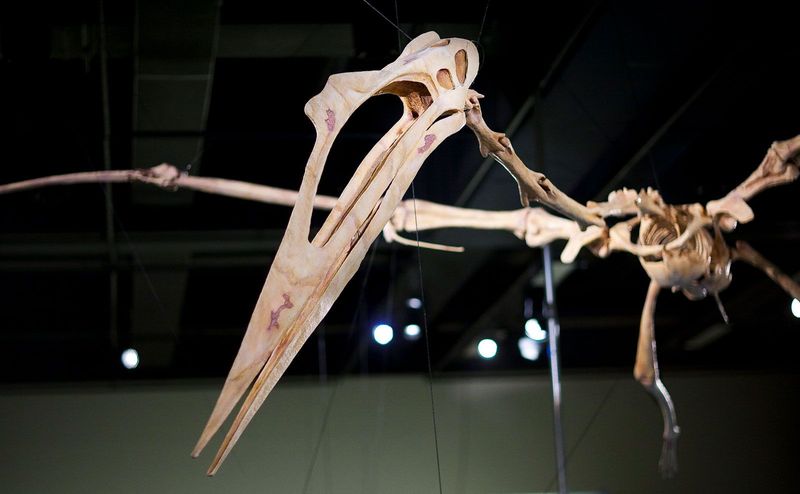

Quetzalcoatlus

Quetzalcoatlus, one of the largest known flying animals, ruled the skies during the Late Cretaceous. With a wingspan reaching 36 feet, this pterosaur was a master of the air.

Its fossils have been crucial in understanding the mechanics of flight in large vertebrates. Quetzalcoatlus likely fed on fish and small animals, using its long beak to snatch prey.

The discovery of its fossils has provided significant insights into the aerodynamics and lifestyle of pterosaurs, enhancing our understanding of avian and reptilian evolution in prehistoric epochs.

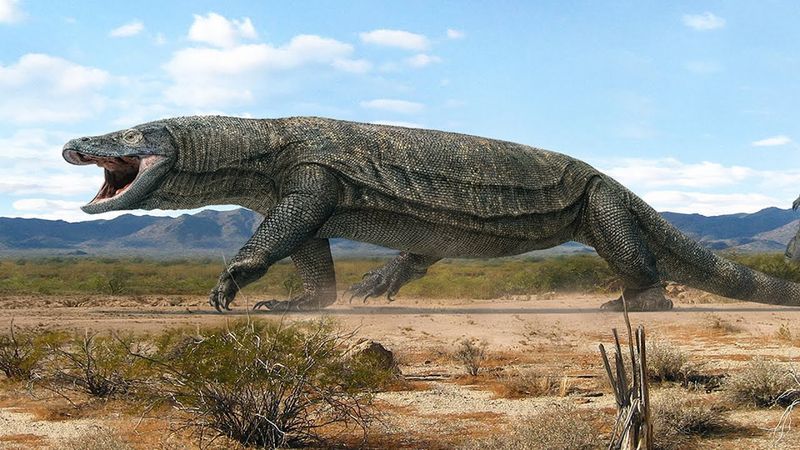

Megalania

Megalania, a giant lizard, once inhabited Pleistocene Australia, reaching lengths of over 23 feet. It was the largest terrestrial lizard, and its presence paints a picture of a bygone era dominated by megafauna.

Fossils indicate it was an apex predator, potentially preying on large marsupials. The study of Megalania fossils has provided insights into the adaptation and evolution of large reptiles in isolated ecosystems.

Understanding its ecological role helps paint a broader picture of Pleistocene megafauna and their interactions within their habitats, offering clues about Australia’s prehistoric biodiversity.

Mammoth

The woolly mammoth, perhaps the most iconic of ancient giants, roamed the cold steppes of Eurasia and North America. These creatures stood up to 11 feet high and weighed up to 6 tons.

They were well adapted to cold climates, with thick fur and long tusks. Fossils and frozen specimens have informed us about their diet, behavior, and the Ice Age environment.

Studying mammoths has provided insights into the effects of climate change on large mammals and their eventual extinction, serving as a crucial point of reference for understanding past and future biodiversity.

Elasmotherium

Elasmotherium, known as the ‘Siberian unicorn,’ was a prehistoric rhinoceros with an enormous horn. Living during the Pleistocene epoch, it roamed the Eurasian steppes.

Fossils suggest it was over 15 feet long and weighed more than 4 tons. Its horn, possibly used for defense or foraging, has sparked much interest. The study of Elasmotherium fossils offers insights into the coexistence and competition of megafauna.

These findings contribute to the understanding of ecological niches and the evolutionary pressures faced by large herbivores in ancient environments.

Andrewsarchus

Andrewsarchus, a colossal carnivorous mammal, lived during the Eocene epoch about 45 million years ago. With a skull over 3 feet long, it was one of the largest terrestrial carnivorous mammals.

Fossils found in Mongolia depict a creature that was likely a top predator. Its enormous jaws suggest a diet of meat and possibly carrion.

Andrewsarchus offers a unique glimpse into the evolution of mammalian carnivores and their dominance in ancient ecosystems, helping scientists understand the dynamics of predator-prey relationships and ecological roles in prehistoric times.

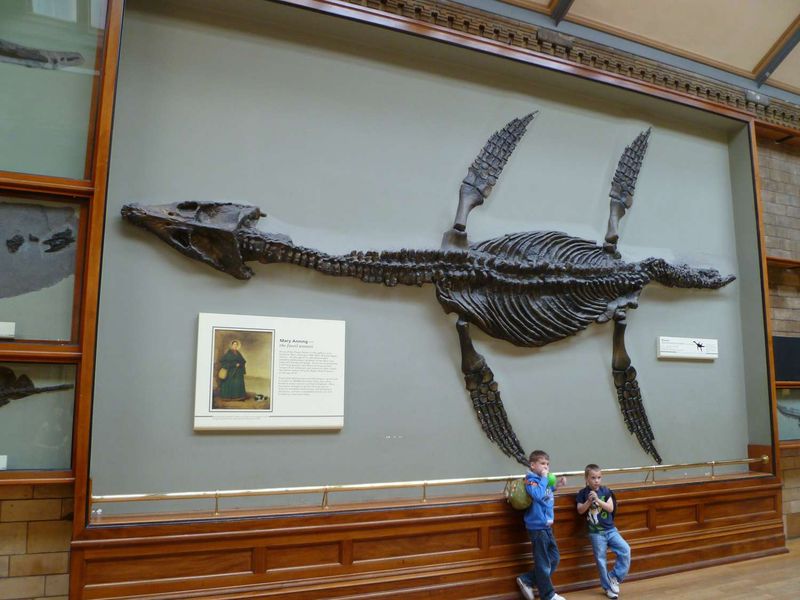

Pliosaurus

Pliosaurus, a massive marine reptile, was a dominant predator in the oceans of the Jurassic period. With a body length exceeding 40 feet, it had a powerful bite capable of hunting large prey.

Fossils reveal its role as an apex predator, shaping the marine ecosystems of its time. The study of Pliosaurus provides valuable information about marine life forms and their interactions in the Jurassic seas.

Insights gained from its fossils have enhanced our understanding of ancient marine biodiversity and the evolutionary pathways of marine reptiles.

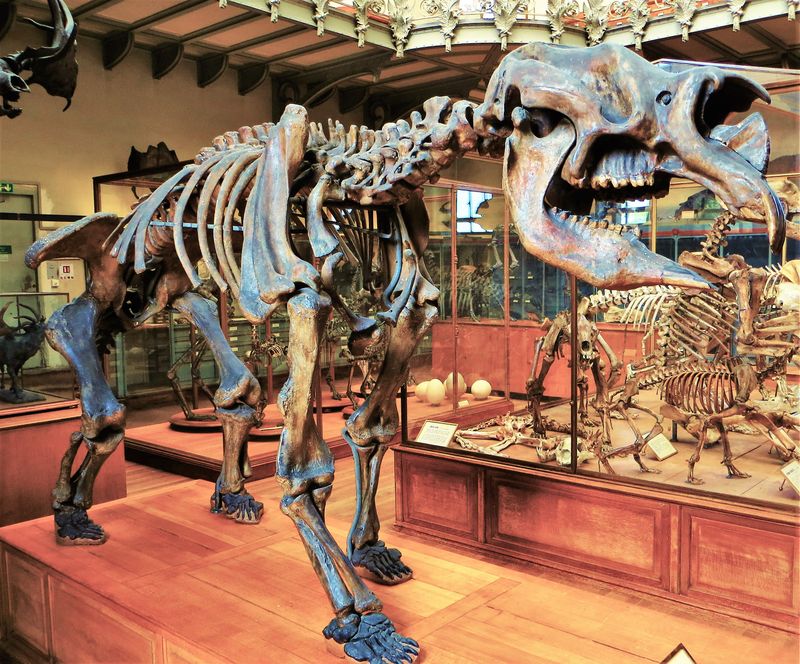

Brontotherium

Brontotherium, a giant mammal from the Eocene epoch, had a body length of around 16 feet. Its distinctive forked horns were likely used in displays and combat. Fossils found in North America provide evidence of its lifestyle and ecological role.

This creature’s size and horn structure offer insights into the evolution of large herbivores. Understanding its life helps scientists decipher the habitat preferences and social behaviors of ancient mammals, contributing to knowledge about the diversity and complexity of Eocene ecosystems and the evolutionary history of large mammals.

Spinosaurus

Spinosaurus, one of the largest carnivorous dinosaurs, roamed the Cretaceous swamps in what is now North Africa. Reaching over 50 feet in length, it was distinctive for its sail-like back structure.

Fossils suggest it was semi-aquatic, preying on fish and other aquatic organisms. The discovery of Spinosaurus has revolutionized our understanding of dinosaur diversity and adaptation.

Its semi-aquatic lifestyle is unique among large theropods, offering insights into the evolutionary pressures and ecological niches that shaped the lives of these prehistoric giants, contributing to a deeper understanding of dinosaur evolution.

Diprotodon

Diprotodon, the largest known marsupial, lived in Australia during the Pleistocene epoch. It could grow up to 14 feet long and weighed over 3 tons. Its fossils have been found across Australia, indicating a widespread distribution.

As a herbivore, it likely played a significant role in shaping the vegetation of its environment. Understanding Diprotodon’s life and extinction provides insights into the impact of climate change and human activities on megafauna.

Fossils of this giant marsupial help scientists explore the evolution and adaptation strategies of large herbivores in isolated ecosystems.

Purussaurus

Purussaurus, a massive caiman, lived in the Miocene epoch in South America. Measuring up to 41 feet long, it was one of the largest crocodilians ever. Fossils suggest it inhabited ancient river systems, preying on large mammals and other reptiles.

Its size and predatory capabilities offer insights into the ecosystem dynamics of Miocene South America. The study of Purussaurus fossils has provided valuable information on the evolutionary history of crocodilians and their adaptation to changing environments, enhancing our understanding of the biodiversity and complexity of prehistoric river ecosystems.