Bulls hate red. Lemmings jump off cliffs. Goldfish have a three-second memory.

Lies. All of it.

Some of the world’s most popular “animal facts” are complete fiction—passed down like bedtime stories with zero proof and a ton of confidence. Somewhere along the way, these myths stuck, and now even adults repeat them like gospel.

The truth? It’s way stranger—and way cooler.

Get ready to unlearn everything your uncle, your teacher, and that one wildlife documentary told you.

From misunderstood predators to totally misrepresented pets, we’re setting the record straight.

Here are 17 animal myths that people still believe… and why they’re totally wrong.

Bats are Blind

Bats, often shrouded in mystery, are mistakenly believed to be blind. In truth, bats see as well as humans do, and they rely heavily on echolocation. This ability allows them to navigate and hunt in complete darkness. The myth stems from their nocturnal habits and unique hunting methods. Many species of bats use this sophisticated sonar system to detect objects as tiny as a human hair in their path. So, the next time you see a bat flying at dusk, remember it’s not flying blind but navigating its world with precision.

Goldfish Have Three-Second Memory

The belief that goldfish only have a three-second memory has been debunked by science. Studies show that goldfish can remember information for months. They can be trained to perform simple tasks and recognize different times of feeding. This myth likely emerged from misunderstanding their behavior in small, unstimulating environments. In reality, goldfish are intelligent creatures capable of learning and memory retention. Providing them with an enriched environment can reveal their true cognitive abilities. So, when you watch your goldfish swim, know it’s more aware than you might think.

Ostriches Bury Their Heads in Sand

The image of an ostrich burying its head in the sand is a popular but incorrect vision. Ostriches never engage in such behavior. This myth likely arose from observing them pecking at the ground or lying down with their heads and necks flat on the ground to avoid detection. In reality, ostriches are vigilant creatures that use their keen eyesight and speed to evade predators. When threatened, they can run at speeds up to 45 miles per hour. So, the next time you hear this saying, remember it’s just a flight of fancy.

Lemmings Commit Mass Suicide

The myth of lemmings committing mass suicide by jumping off cliffs was popularized by documentaries in the mid-20th century. Contrary to this grim narrative, lemmings do not engage in such behavior. They migrate in search of food, and sometimes accidental deaths occur by falling over cliffs. This misconception was further fueled by media portrayals. Lemmings are small rodents driven by survival instincts, not self-destructive tendencies. When considering lemmings, think of resilience and adaptability rather than misguided myths.

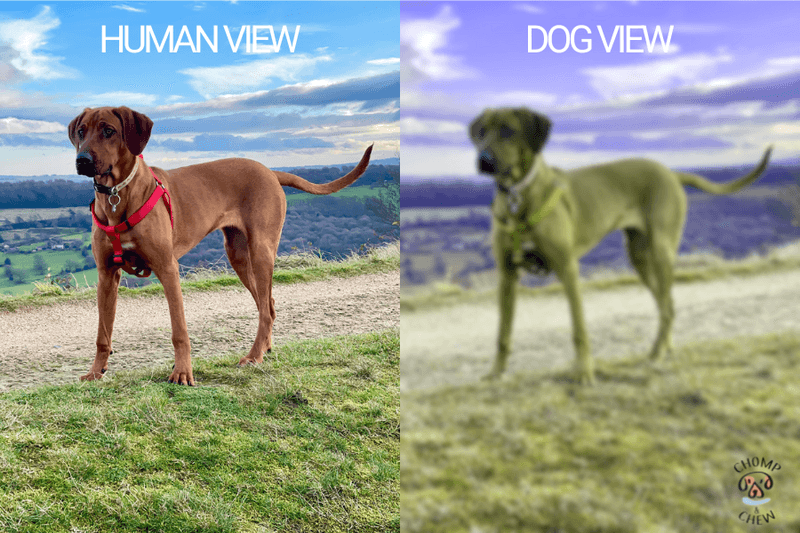

Dogs See Only in Black and White

The notion that dogs see only in black and white is a common misconception. While dogs do not perceive a full spectrum of colors like humans, they can see shades of blue and yellow. This limited color vision is due to having fewer color receptors in their eyes. Despite this, dogs rely on other senses like smell and hearing to understand their environment. So next time you play fetch with your dog in a vibrant park, remember that it enjoys a world that’s more colorful than you might have thought.

Camels Store Water in Their Humps

Camels are often associated with deserts and survival, leading to the myth that they store water in their humps. In reality, their humps are reserves of fatty tissue, which can be converted into energy. Camels are incredibly adapted to conserve water, enduring long periods without it. They can drink up to 40 gallons of water in one go but store it in their bloodstream, not their humps. This unique physiological adaptation allows them to thrive in harsh environments. Thus, camels exemplify nature’s remarkable ingenuity.

Bulls Hate the Color Red

The idea that bulls hate red is a bullfighting myth. Bulls, like all cattle, are color blind to red. It’s the movement of the matador’s cape, not the color, that provokes the bull. The cape’s color is traditional, not functional. Bulls are generally reactive to movement and threats, not colors. This myth persists due to cultural portrayals. In reality, bullfighting involves complex interactions beyond just a color cue. Understanding these animals requires looking past the simplistic myths to their natural behaviors.

Touching a Baby Bird Will Make the Parents Reject It

Many people believe that touching a baby bird will cause its parents to abandon it—a myth rooted in the idea that birds will detect human scent. However, most birds have a limited sense of smell. Parent birds will continue to care for their chicks even if they have been handled by humans. This myth possibly originated as a cautionary tale to prevent handling of young wildlife. While it’s always best to leave wildlife alone, a brief encounter won’t cause rejection by parent birds.

Sharks Don’t Get Cancer

The myth that sharks don’t get cancer stems from a belief in their evolutionary superiority, but it’s not true. Sharks can and do develop cancer. This misconception was popularized by misleading studies and claims to sell supplements. Sharks’ unique cartilage structure fueled these myths, although no scientific basis supports them being cancer-free. Despite their impressive survival skills and adaptations, sharks face threats like cancer, just as other species do. Recognizing the myth helps us better appreciate these ancient ocean dwellers’ true biological complexities.

Chameleons Change Color to Match Their Surroundings

Chameleons are famous for their color-changing abilities, but they don’t do it primarily for camouflage. Instead, color changes reflect their mood, temperature, and communication needs. Their skin contains special cells that can expand or contract to reveal different pigments, creating various colors. This ability is more about social signaling and temperature regulation than blending into backgrounds. Understanding chameleons involves appreciating their unique biology and behavioral complexities, not just their ability to change colors.

Bears Hibernate All Winter Long

Contrary to popular belief, bears do not hibernate in the true sense. They enter a state of torpor, which is less intense than hibernation. During this period, bears’ metabolism slows, and they do not eat, drink, or pass waste frequently. However, they can wake up and become active if disturbed or if conditions change. This ability distinguishes them from hibernators like groundhogs. Understanding this aspect of bear biology highlights their adaptability and survival strategies in harsh climates.

Owls are Wise

Owls are often depicted as symbols of wisdom, a notion rooted in ancient mythology. However, their intelligence is not superior to other birds. Owls are skilled hunters with excellent night vision and hearing, traits that have contributed to this reputation. Their silent flight and ability to locate prey make them fascinating creatures, but not necessarily wiser. This myth persists because of cultural associations. Understanding owls’ true talents allows us to appreciate their unique adaptations and hunting prowess.

Toads Cause Warts

The belief that toads cause warts is a persistent myth with no basis in reality. Toads have bumpy skin that may look like warts, but they do not transmit them. Warts in humans are caused by viruses, not contact with toads. This myth likely arose from fear and misunderstanding of amphibians’ appearances. In reality, toads play crucial roles in ecosystems as pest controllers. Dispelling this myth helps foster a more appreciative view of these helpful creatures, rather than unfounded fears.

Lions are the King of the Jungle

Lions, often called the ‘king of the jungle,’ actually inhabit savannas and grasslands, not jungles. This title reflects their majestic appearance and social structure rather than habitat. Lions live in prides, with intricate social dynamics, where females do most of the hunting. Their role as apex predators is undisputed, but the ‘jungle’ misnomer persists due to historical and cultural factors. Appreciating lions involves understanding their true habitat and remarkable social behaviors, which are as impressive as their regal image.

Penguins Mate for Life

The romantic notion that penguins mate for life is a charming but oversimplified myth. While some species form long-term pair bonds, others may change partners between breeding seasons. This flexibility in mating strategies ensures genetic diversity and adaptation to changing environments. Penguins’ social structures and behaviors are complex, shaped by environmental pressures. Understanding these nuances provides a deeper insight into their lives beyond romanticized myths. These birds’ resilience and adaptability make them even more fascinating.

Elephants Never Forget

Elephants are renowned for their memory, leading to the saying that they ‘never forget.’ While elephants have excellent memories, especially for social relationships and migration routes, they do forget like any other animal. Their complex brains support strong social bonds and problem-solving abilities. This myth reflects their impressive cognitive abilities but oversimplifies their true capacities. Recognizing elephants’ intelligence involves understanding their social nature and environmental interactions. Their ability to remember and connect is indeed remarkable, though not infallible.

Porcupines Can Shoot Their Quills

Porcupines, with their distinct quills, might seem like nature’s archers. However, contrary to popular belief, they cannot shoot their quills. These quills are actually modified hairs that detach easily when a predator makes contact. Surprisingly, the quills have barbs that can embed into an attacker’s skin, causing discomfort.

A quill’s defensive capability lies in its ability to detach, not in being launched. Touching a porcupine can lead to a painful experience, but only through direct contact. Fun fact: porcupines often rattle their quills to warn potential threats, a behavior akin to a rattlesnake’s warning rattle.