Throughout history, Earth has witnessed the rise and fall of countless species. Some animals have left behind fossils and tales, sparking our imagination and scientific curiosity.

This blog post highlights 13 extinct mammals that once roamed our planet, showcasing the diversity and wonder that nature holds. These creatures are reminders of a world we can only glimpse through scientific discovery and the stories we tell.

Woolly Mammoth

This colossal creature roamed the icy plains of the northern hemisphere thousands of years ago. Its thick, shaggy fur and enormous tusks were adapted to the frigid climate.

Inhabiting regions now known as Siberia and North America, it has become an iconic symbol of the Ice Age fauna. The mammoth’s diet consisted mainly of grasses, which it grazed on in large herds.

Unfortunately, climate change and human hunting pressures contributed to its extinction. Today, scientists are exploring de-extinction possibilities, aiming to revive this majestic giant using advanced genetic techniques.

Tasmanian Tiger

Known also as the Thylacine, this marsupial predator once roamed Tasmania, New Guinea, and mainland Australia. With dog-like features and a pouch similar to kangaroos, it captivated those who encountered it.

Its distinctive striped back added to its unique appearance. Despite its fierce look, it was shy and nocturnal, hunting small animals to survive.

The last known individual died in captivity in 1936. Deforestation, hunting, and disease contributed to its rapid decline.

Efforts continue today to investigate sightings and possibly resurrect its genetic lineage.

Saber-Toothed Cat

With its elongated canine teeth, this predator dominated the landscapes during the Pleistocene epoch. Its powerful build and fearsome appearance made it a formidable hunter.

These cats hunted large herbivores, using their fangs to deliver fatal bites. Found across the Americas, they thrived in diverse environments from forests to grasslands.

As the climate changed and prey became scarce, their numbers dwindled. Paleontologists continue to unearth fossils, giving us insights into their lives.

The saber-toothed cat remains a symbol of prehistoric might.

Irish Elk

The Irish Elk was renowned for its spectacular antlers, spanning up to 12 feet across. Native to Eurasia, it was not an elk but a giant deer.

These creatures preferred open woodlands and grasslands, browsing on shrubs and grasses. Their impressive size and antlers made them a target for human hunters.

As the Ice Age ended, changing habitats and human activity contributed to their extinction. Fossils and antler specimens continue to fascinate researchers.

The Irish Elk serves as a reminder of nature’s grandeur and the fragility of life.

Giant Ground Sloth

Massive and slow-moving, these herbivores were among the largest land mammals. Their size and strength allowed them to topple trees to access food.

Inhabiting South and North America, they thrived in diverse habitats. The sloths’ disappearance coincides with the arrival of humans, suggesting overhunting as a factor in their extinction.

Fossils reveal their unique adaptations, such as long claws for digging and defense. These gentle giants are a testament to the variety of life that once existed, showing nature’s ability to produce extraordinary creatures.

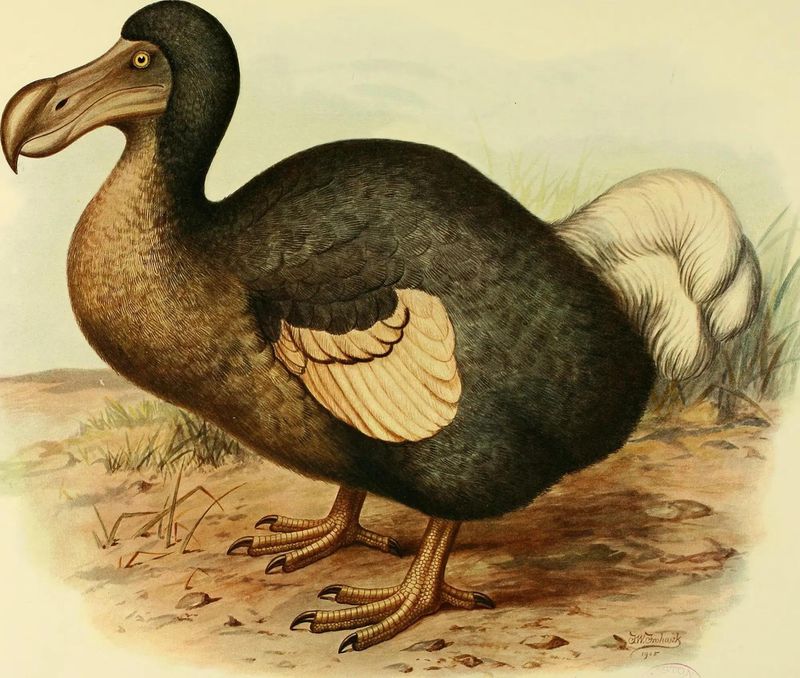

Dodo

Though not a mammal, the flightless dodo is often associated with discussions on extinction. Native to Mauritius, these birds were unafraid of humans, making them easy targets.

Their extinction in the late 17th century was rapid, driven by hunting and introduced species. The dodo’s downfall is a classic example of human-induced extinction.

Despite their ungainly appearance, they played a vital role in their ecosystem. Today, the dodo serves as a symbol of extinction awareness, reminding us of the impact human activity can have on other species.

Quagga

Resembling a zebra, the quagga was unique with its half-striped, half-solid brown coat. Native to South Africa, it was social and lived in herds.

Once abundant, excessive hunting by European settlers led to their extinction in the late 19th century. The last known quagga died in an Amsterdam zoo in 1883.

Conservation efforts are underway to rebreed this animal from selective zebra breeding. The quagga’s story highlights the impact of unchecked hunting and the potential for modern science to restore lost wonders.

Thylacoleo

Known as the marsupial lion, Thylacoleo was a unique predator in ancient Australia. It possessed retractable claws and a powerful bite, preying on large herbivores.

Despite being called a lion, it was more closely related to wombats and koalas. This creature roamed forests and open plains, adapting to varied environments.

As humans arrived in Australia, their impact through hunting and habitat change likely contributed to its extinction. Fossil discoveries continue to provide insights into its lifestyle and ecological role, enriching our understanding of Australia’s prehistoric fauna.

Harlan’s Ground Sloth

This massive creature belonged to the same family as the giant ground sloth but was slightly smaller. It inhabited North America, particularly in areas now known as Texas and Mexico.

Their robust bodies and strong limbs helped them in foraging. Human activities and climate shifts marked the end of their era.

Fossils continue to be unearthed, revealing details about their diet and lifestyle. Harlan’s ground sloth exemplifies the diverse adaptations mammals developed to thrive in different ecosystems, even in challenging environments.

Steller’s Sea Cow

Once populating the Bering Sea, Steller’s sea cow was a gentle marine mammal. Related to the manatee, it was much larger, reaching lengths of up to 30 feet.

Its docile nature made it vulnerable to human hunters, and within 27 years of its discovery in 1741, it was hunted to extinction. The species fed on kelp and played a role in maintaining the health of marine ecosystems.

Its loss is a reminder of how quickly human exploitation can eradicate a species. Efforts to protect marine life continue today in its memory.

Balearic Shrew

This tiny insectivore was endemic to the Balearic Islands, living in a unique insular environment. Its survival was intricately linked to the delicate ecosystems of the islands.

As humans colonized these islands, habitat destruction and introduced predators led to its extinction. The Balearic shrew is a prime example of the vulnerability of island species.

Although gone, its story underscores the importance of protecting remaining island habitats. Conservationists use such cases to highlight the need for preserving biodiversity and preventing future losses.

Western Black Rhinoceros

A subspecies of the black rhinoceros, it was once found in several African countries. Poaching for its horn led to its rapid decline, with the last confirmed sighting in Cameroon during 2006.

Conservationists mourn its loss as a failure to protect one of nature’s magnificent creatures. The Western black rhinoceros’ story is a stark reminder of the ongoing threats faced by rhino populations globally.

Efforts to protect other rhino species continue, focusing on anti-poaching measures and habitat preservation to prevent further extinctions.

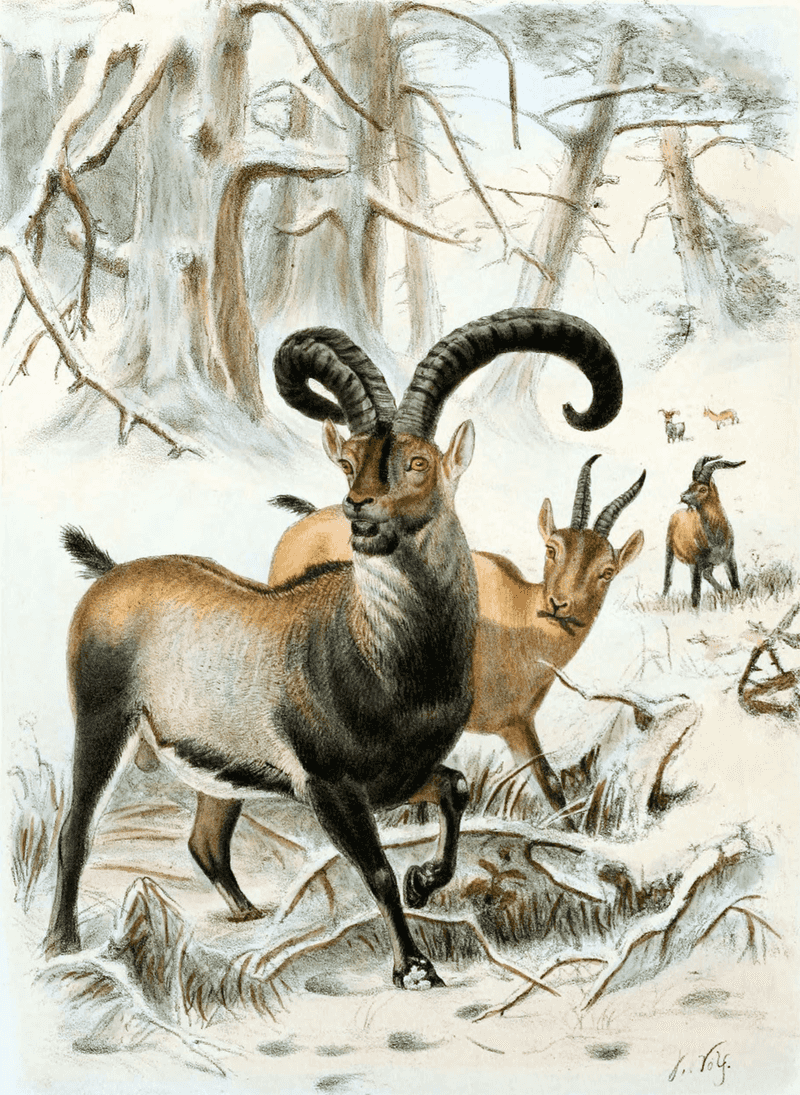

Pyrenean Ibex

This mountain goat was native to the Pyrenees, gracefully navigating rocky terrains. It adapted well to its harsh environment but fell victim to hunting and habitat loss.

The last known individual died in 2000, marking a poignant end to its kind. In a groundbreaking scientific effort, a clone was created in 2003, albeit surviving only briefly.

This attempt at de-extinction highlights the potential and challenges of reviving lost species. The Pyrenean ibex’s tale is one of resilience and scientific curiosity, pushing the boundaries of what is possible.